Retrospective study of patients with asymptomatic, incidentally discovered, thoracic aortic pseudoaneurysm treated in a single institution

| Available Online: | January, 2025 |

| Page: | 8–15 |

Author for correspondence:

Nikolaos Kontopodis, MD, MSc, PhD

University of Crete, Medical School, Heraklion, Greece

Tel: +30 6948202539, +30 2810 392379

E-mail: kontopodisn@yahoo.gr, nkontopodis@uoc.gr

ISSN 2732-7175 / 2025 Hellenic Society of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Published by Rotonda Publications

All rights reserved. https://www.heljves.com

Abstract

Full Text

References

Images

Abstract

Introduction

Spontaneous thoracic aortic rupture can lead to catastrophic complications. In rare instances, such an event may occur without any symptoms, making it difficult to diagnose and posing an immediate threat to the patient’s life.

Methods

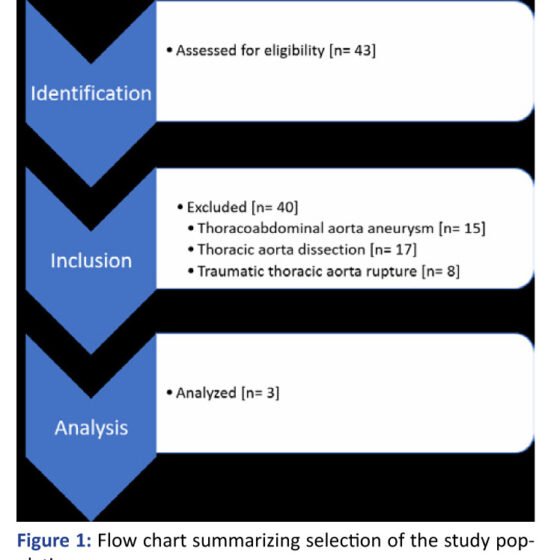

A single-center retrospective analysis was conducted, including all patients who underwent thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) for various pathologies between January 2019 and January 2024. From this cohort, the subgroup of patients with incidentally discovered pseudoaneurysms of the thoracic aorta was identified and further analyzed. Demographic information, procedural details, and follow-up data for these cases were collected and reviewed.

Results

A total of 40 patients were initially identified, of whom only three met the criteria for an incidental finding of a spontaneous, concealed, asymptomatic rupture of the descending thoracic aorta, presenting as a pseudoaneurysm detected on computed tomography (CT) performed for unrelated medical reasons. All three patients were treated on an emergency basis using TEVAR. Branched endografts and chimney techniques were used in two of the three cases. In one patient, a proximal extension with a branched endograft was required to treat a type IA endoleak following an initial standard TEVAR procedure. There was one in-hospital mortality, attributed to unrelated medical causes.

Conclusion

An asymptomatic presentation of a thoracic aortic pseudoaneurysm is possible and may occur incidentally. In such cases, prompt endovascular repair using TEVAR can effectively minimize the risk of severe complications or death.

Full Text

INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous rupture of the thoracic aorta is a devastating event. Most commonly it presents with hemodynamic collapse of the patient, requiring immediate treatment. However, concealed, asymptomatic rupture can be challenging to diagnose, as it may present with atypical symptoms or be completely asymptomatic and be identified as an incidental radiological finding days, weeks or even months after the event. This clinical entity poses a unique threat for the patient, as he is unaware of the pathology and the potential complications can be life-threatening. The first 24h mortality of patients with contained rupture of a thoracic aortic aneurysm is around 80%.

As stated by the ACC/AHA 2022 Guidelines, a pseudoaneurysm of the thoracic aorta following a blunt traumatic thoracic aortic injury [BTTAI] is classified as Grade 3 BTTAI and should be managed urgently, as they are at a high risk of progression and rupture. However, in the present study incidental finding of non-traumatic thoracic aortic pseudoaneurysm was our focus. To our knowledge, data are very limited regarding pathophysiology, natural history, and prognosis of this clinical entity and consequently robust diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms are not currently available.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design:

We conducted a retrospective observational study of all patients treated with TEVAR, in our department, between 01/2019 – 01/2024, according to the STROBE statement for observational studies. Our study population consisted of patients treated for an asymptomatic, incidentally found thoracic aorta pseudoaneurysm.

Inclusion criteria:

All patients with thoracic aortic pathology undergoing interventional treatment throughout the study period were identified. This included patients with thoracic aortic aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm, thoracoabdominal aneurysms, patients with acute aortic syndromes that involved the thoracic aorta [aortic dissection – AD, intramural hematoma – IMH, penetrating aortic ulcer – PAU or thoracic aorta rupture] and also patients with acute thoracic aortic injuries after blunt or penetrating trauma.

After the initial screening, only patients with an incidental finding of a thoracic aortic pseudoaneurysm were analyzed.

Exclusion criteria:

Patients with aortic pathology that did not involve the descending thoracic aorta were excluded [for example, pathology including the ascending aorta, abdominal aorta and iliac arteries]. Additionally, patients with thoracic aortic pathologies that were managed conservatively were also excluded.

Endpoints:

Information that were collected included patients’ demographic characteristics [age, gender, ethnicity], comorbidities and past medical history, clinical presentation, the modalities that were used for the diagnosis, the lesions’ characteristics [meaning its’ diameter, neck length, aortic branches involved] and type of treatment, including treatment technical characteristics. Endpoints included technical and clinical success, need for re-intervention, length of hospital stay and/or need for stay in the ICU, patients’ mortality and morbidity and follow-up outcomes.

RESULTS

Study population:

After searching our database, 43 patients were at first identified. Fifteen patients were treated for thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm, 17 patients presented with thoracic aortic dissection treated either in the acute or subacute phase and 8 patients presented contained aortic rupture after trauma and were subjected to endovascular repair. Finally, 3 patients fulfilled the criteria for an asymptomatic, incidentally found, thoracic aortic pseudoaneurysm, who were treated with TEVAR.

Overall results:

All patients were treated <24h after initial diagnosis. One patient was treated with Chimney TEVAR, while the remaining two were initially treated with standard TEVAR, with LSA coverage in order to achieve an adequate proximal seal. In one of those cases this was not successful and the deployment of an additional branched device was required to treat a Type IA endoleak. Post-procedurally all patients were admitted to the ICU. Two patients were discharged in good general condition, while one patient died after several weeks of hospitalization due to unrelated medical reasons.

CASE 1

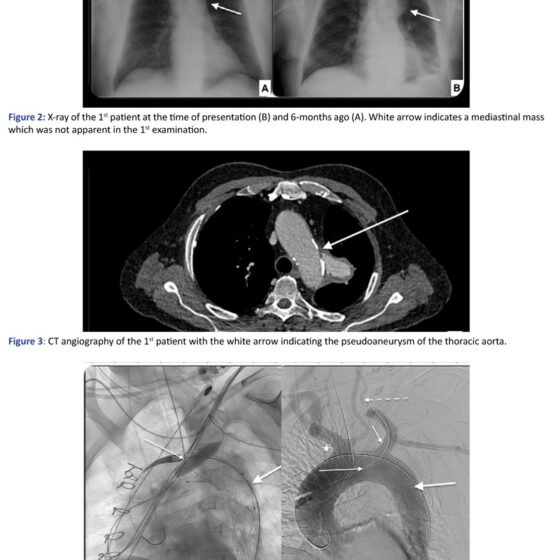

The first patient is a 78 years old male who was hospitalized two months ago for fever of unknown origin, which was finally attributed to lung infiltrations. During his hospitalization he underwent chest x-ray, where a radiopaque saccular mass in the left mediastinum was depicted, and which wasn’t present in a previous x-ray from the patient’s history six months ago. However, at that time, this finding wasn’t further assessed. After his discharge, he was advised to undergo a CT scan, in order to review the aforementioned lung infiltrations. In the CT scan a pseudoaneurysm of the thoracic aorta was identified, measuring 60mm of maximum diameter. Then, he was referred to our department where he underwent CT angiography [CTA] and a concealed rupture of the thoracic aorta, originating proximal to the origin of the left subclavian artery [LSCA] was diagnosed. Specifically, a ruptured penetrating aortic ulcer [PAU] was identified as the probable cause of rupture.

He was treated urgently with chimney – TEVAR [Ch-TEVAR] under general anaesthesia. A TEVAR endograft Terumo RelayPro 34/30 154mm was deployed with the proximal extent in the Z2 zone, just proximal to the origin of the LSCA and distal extent to T5 zone, while two balloon expandable covered stents Atrium Advanta V12 [BE] 12x61mm were deployed in the LSCA, with the chimney technique, in order to preserve LSCA patency. The patient had a high-grade left internal carotid artery stenosis, measured around 90%, so assuring that the left vertebral artery remained patent was important in order to preserve brain perfusion.

The patient was transferred post-operatively to the ICU, awake, for further monitoring where he remained for 24h and then was transferred to the Vascular Surgery Unit in good general condition. During his hospitalization he developed contrast-induced acute kidney injury [CI-AKI], which prolonged his stay for five days. The fourth postoperative day the patient underwent a CTA for post-operative monitoring, where a gutter endoleak between the main endograft and the Chimney graft was identified, without clinically significant growth of the aneurysm diameter. A third scan was performed during the eighth postoperative day for investigation of an episode of shortness of breath, where spontaneous occlusion of the endoleak was observed, without growth of the pseudoaneurysm sac. He was discharged the ninth post-op day, with baseline renal function restored. The patient has successfully completed short-term follow-up, at one month after the discharge, where no endoleak and sac regression were identified.

CASE 2

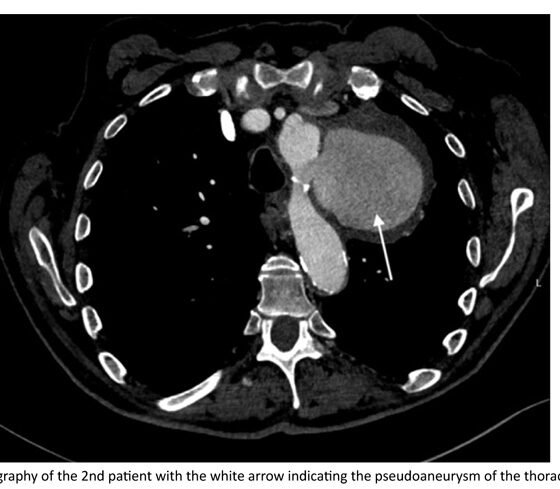

The second patient was a 73 years old male with a history of lung lymphoma with multiple chemo- and radiation-therapy sessions, who was at that time hospitalized in the Hematology department for dyspnea, cough and hoarseness of voice investigation. He underwent non-contrast thorax CT for possible respiratory tract infection. However, in the CT scan, a pseudoaneurysm of the descending thoracic aorta was identified. Following this finding, the patient underwent CTA, where a concealed rupture of the thoracic aorta, originating distal to the origin of the LSCA was diagnosed, with a pseudoaneurysm measuring 85mm of maximum diameter.

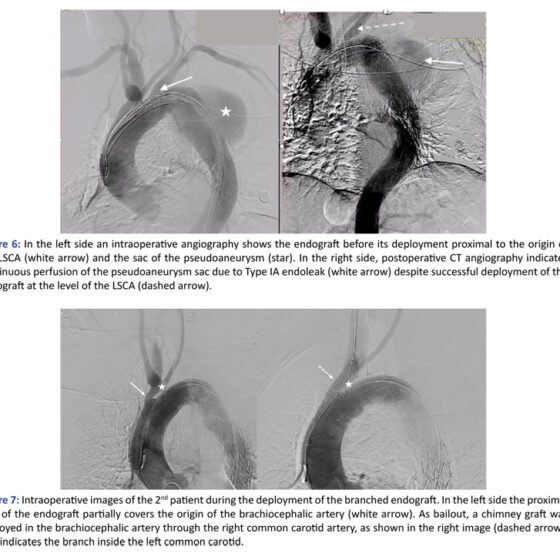

He was treated urgently with TEVAR endograft Terumo RelayPro 32/32x160mm. In the completion angiography, a Type IA endoleak was depicted, and therefore the patient underwent a second procedure 24h later, with the insertion of a proximal extension of the endograft with the deployment of a Castor Endograft EndovasTec Lombard 36/30x200mm with a branch to the left common carotid artery [LCCA]. During the deployment, the endograft slightly migrated proximally, causing severe stenosis of the orifice of the brachiocephalic artery [BCA]. Immediately, the right common carotid artery [RCCA] was dissected and cannulated and a balloon expandable covered stent Atrium V12 12x61mm was deployed in the BCA with the chimney technique.

Postoperatively, he had a prolonged stay at the ICU due to severe face and larynx swelling which didn’t allow extubation. Moreover, the patient acutely developed severe heart failure, with a left ventricle ejection fraction [LVEF] 15% and multiple episodes of acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS], which were finally attributed to bronchiolitis. The patient was transferred to the Pulmonology department for further treatment on the forty-ninth post-op day. However, he passed away ten days later due to aplastic anemia and acute respiratory failure.

CASE 3

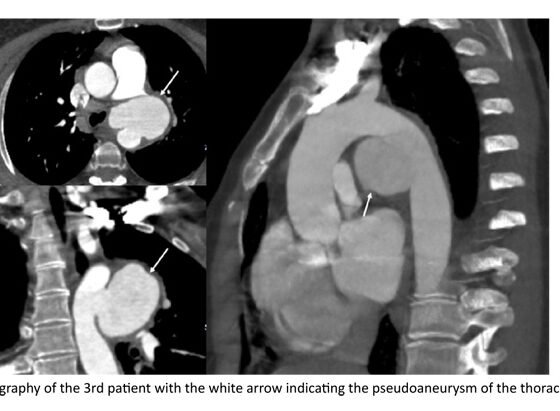

The third patient is a 44 years old female, with a history of Adamantiades – Behcet’s disease [ABD], under therapy with colchicine and methotrexate, who was hospitalized in the Pulmonology department for thoracic pain migrating to the back and possible upper respiratory tract infection. During her hospitalization she underwent a non-contrast thorax CT. The CT showed a periaortic hematoma in junction with the descending thoracic aorta, described as a potential concealed rupture of the thoracic aorta forming a saccular pseudoaneurysm measuring 60mm of maximum diameter.

She underwent urgent TEVAR under general anaesthesia. A TEVAR endograft Terumo Relay PRO 28x130mm, with proximal extent to the Z2 zone, just proximal to the LSCA and distal extent to T5 zone, was deployed. In the completion angiography, adequate coverage of the rupture point was verified, while LSCA and left vertebral artery remained patent, without endoleak or active extravasation. Her postoperative course was uncomplicated and she was discharged on the fourteenth post-op day. The patient has completed three-year follow-up, with complete sac regression in the most recent CTA.

DISCUSSION

After conducting a detailed search of all patients treated in our department for pathology regarding the thoracic aorta during the last five years, we identified three patients that fulfilled the aforementioned criteria and formed our target-group.

The first patient suffered a concealed spontaneous rupture of the descending thoracic aorta due to a ruptured penetrating aortic ulcer [rPAU]. The second patient had lymphoma in regression, while the third patient had Behcet’s disease, illustrating the heterogeneity of underlying conditions that may lead to pseudoaneurysm formation.

Post-TEVAR type IA endoleak was identified in two of the three patients. Endoleak can be found in up to 9–38% of TEVAR cases, with type I being the most common. All type IA endoleaks should be treated, since they represent high-pressure leaks that can cause sac expansion, rupture, and death. However, some may resolve spontaneously.

Patient #1 developed acute-on-chronic kidney disease but recovered fully with management. Patient #2 developed acute severe heart failure (LVEF 15%) and recurrent ARDS episodes without signs of acute coronary syndrome. In the literature, after TEVAR, an increase of arterial stiffness is noted, with multiple effects in the heart, central hemodynamics and heart systole. However, such acute and severe HF was an unexpected complication in this case and burdened heavily his postoperative course.

CONCLUSION

Spontaneous, asymptomatic rupture of the thoracic aorta is a rare vascular condition. Patients with different medical backgrounds may present with such lesions. In the absence of robust evidence regarding the clinical course of these cases, prompt endovascular treatment — even if performed under suboptimal conditions, without waiting for a complete preoperative work-up — may be appropriate in order to treat these patients and avoid serious adverse events.

References

1. Kasahara H, Hachiya T, Mori A. Emergency Endografting for Spontaneous Thoracic Aortic Rupture. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;27:68-70.

2. Lau C, Leonard JR, Iannacone E, Guadino M, Girardi LN. Surgery for acute presentation of thoracoabdominal aortic disease. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;31:11-6.

3. Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J 3rd, Augoustides JG, Beck AW, Bolen MA, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association / American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;146:e334-e482.

4. Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al; STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1500-24.

5. Dev R, Gitanjali K, Anshuman D. Demystifying penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer of aorta: unrealised tyrant of senile aortic changes. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2021;13:1-14.

6. Lansman S, Saunders P, Malekan R, Spielvogel D. Acute Aortic Syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140(6 Suppl):S92-7.

7. Lee WMM, Wong OF, Fung HT. Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer—an increasingly recognised entity of the acute aortic syndrome: case report and literature review. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2009;16:246-251.

8. Kyaw H, Sadiq S, Chowdhury A, Gholamrezaee R, Yoe L. An uncommon cause of chest pain—penetrating atherosclerotic aortic ulcer. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2016;6:31506.

9. Eckholdt C, Pennywell D, White RK, Perkowski PE. Unusual presentation of acute ruptured penetrating aortic ulcer of descending thoracic aorta with right hemothorax. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech. 2023;9:101176.

10. Becker von Rose A, Kobus K, Bohmann B, Lindquist-Lilljequist M, Eilenberg W, Bassermann F, et al. Radiation and Chemotherapy are Associated with Altered Aortic Aneurysm Growth in Patients with Cancer: Impact of Synchronous Cancer and Aortic Aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2022;64:255-264.

11. Danial P, Crawford S, Mercier O, Mitilian D, Girault A, Haulon S, et al. Primary Thoracic Endografting for T4 Lung Cancer Aortic Involvement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2023;115:542-546.

12. Metzger PB, Costa KR, Metzger SL, de Almeida LC. Endovascular treatment of aortic saccular aneurysms associated with Adamantiades-Behçet disease. J Vasc Bras. 2021;20:e20200201.

13. Riambau V, Böckler D, Brunkwall J, Cao P, Chiesa R, Coppi G, et al. Editor’s Choice – Management of Descending Thoracic Aorta Diseases: Clinical Practice Guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017;53:4-52.

14. Nation DA, Wang GJ. TEVAR: Endovascular Repair of the Thoracic Aorta. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2015;32:265-71.

15. Valente T, Rossi G, Lassandro F, M Marino, G Tortora, R Muto, et al. MDCT in diagnosing acute aortic syndromes: reviewing common and less common CT findings. Radiol Med. 2012;117:393-409.

16. Bhave N, Nienaber C, Clough R, et al. Multimodality Imaging of Thoracic Aortic Diseases in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2018;11:902-919.

17. Pierro A, Posa A, Iorio L, Tanzilli A, Cucciolillo L, Quinto F, et al. Bib Sign in Proximal Descending Thoracic Aorta Rupture on CT Angiography: Presentation of a Paradigmatic Case. Case Rep Radiol. 2022:6947207.

18. Rivera PA, Dattilo JB. Pseudoaneurysm. 2024 Feb 17. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

19. Ricotta JJ 2nd. Endoleak management and postoperative surveillance following endovascular repair of thoracic aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52(4 Suppl):91S-9S.

20. De León Ayala IA, Cheng YT, Chen SW, Chu SY, Nan YY, Liu KS. Outcomes of type Ia endoleaks after endovascular repair of the proximal aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2022;163:2012-2021.

21. Azevedo AI, Braga P, Rodrigues A, Ferreira N, Fonseca M, Dias A, Gama Ribeiro V. Persistent Type I Endoleak after Endovascular Treatment with Chimney Technique. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2016;3:32.

22. Kapalla M, Kröger J, Choubey R, Busch A, Hoffmann RT, Reeps C, et al. Outcome of Endovascular and Open Treated Penetrating Aortic Ulcers. J Endovasc Ther. 2024 Mar 27:15266028241241205.

23. Stacul F, van der Molen AJ, Reimer P, Webb JA, Thomsen HS, Morcos SK, et al. Contrast induced nephropathy: updated ESUR Contrast Media Safety Committee guidelines. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:2527-41.

24. Lameire N, Kellum JA. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury and renal support for acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary (part 2). Crit Care. 2013;17:205.

25. Geisbüsch P, Kotelis D, Müller-Eschner M, Hyhlik-Dürr A, Böckler D. Complications after aortic arch hybrid repair. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:935-41.

26. Moulakakis KG, Pitros CF, Theodosopoulos IT, Mylonas SN, Kakisis JD, Manopoulos C, Kadoglou NPE. Arterial Stiffness and Aortic Aneurysmal Disease – A Narrative Review. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2024;20:47-57.

27. Marketou M, Papadopoulos G, Kontopodis N, Patrianakos A, Nakou E, Maragkoudakis S, et al. Early Left Ventricular Global Longitudinal Strain Deterioration After Aortic Aneurysm Repair: Impact of Aortic Stiffness. J Endovasc Ther. 2021;28:352-359.