Rupture of the infrarenal aorta during the 1st postoperative day after emergent endovascular treatment of acute Type B aortic dissection

| Available Online: | January, 2025 |

| Page: | 21–24 |

Author for correspondence:

Nikolaos Kontopodis, MD, MSc, PhD

University of Crete, Medical School, Heraklion, Greece

Tel: +30 6948202539, +30 2810 392379

E-mail: kontopodisn@yahoo.gr, nkontopodis@uoc.gr

ISSN 2732-7175 / 2025 Hellenic Society of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Published by Rotonda Publications

All rights reserved. https://www.heljves.com

2Anesthesiology Department, School of Medicine, University of Crete, Heraklion, Greece

Abstract

Full Text

References

Images

Abstract

Acute Type B Aortic Dissection (ATBAD) is a vascular emergency requiring prompt diagnosis and treatment to avoid serious complications. Complicated cases are treated invasively, preferably by endovascular means.

We present a 60-year-old woman who was admitted due to ATBAD, with the primary entry tear located just distal to the level of the Left Subclavian Artery (LSA) origin. She was initially treated conservatively; however, on the 2nd day, due to refractory pain, she was subjected to emergency TEVAR with LSA coverage.

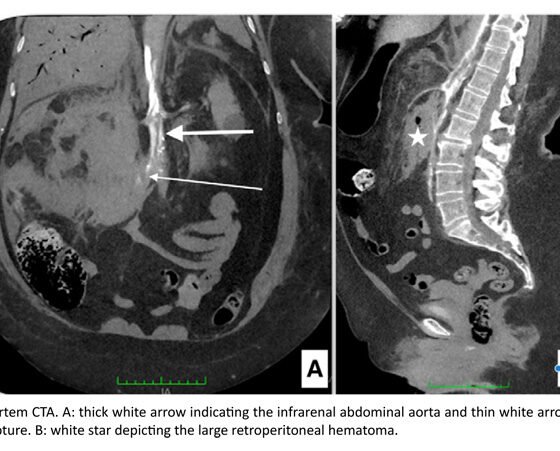

The procedure was uneventful. During the 1st postoperative day, the patient complained of back pain and underwent a new CT, which indicated successful endograft deployment without remarkable changes in the distal thoracic and abdominal aorta compared to the preoperative imaging. During the same night, the patient became hemodynamically unstable and died. Post-mortem CT indicated infra-renal aortic rupture.

ATBAD may result in mortality even if prompt treatment has been undertaken.

Full Text

INTRODUCTION

Acute aortic syndromes are disorders of the thoracic and abdominal aorta that require urgent evaluation and treatment, with acute aortic dissection (AD) being the most frequent and most lethal among them. Uncomplicated Acute Type B Aortic Dissections (ATBAD) initially undergo conservative management with close monitoring in an intensive care unit (ICU) setting, aiming to lower blood pressure and heart rate, relieve pain, and allow for an uneventful recovery during the acute phase. On the contrary, complicated cases (rupture, malperfusion, aortic enlargement) undergo immediate endovascular repair. Similarly, patients with uncontrolled hypertension or refractory pain are considered an intermediate-risk category and are candidates for emergent treatment. The primary goal of endovascular repair is primary entry tear coverage, to lower false lumen pressure, allow true lumen expansion, and promote positive aortic remodeling. Nevertheless, reentry tears may continue to perfuse the false lumen, leading to its expansion.

CASE REPORT

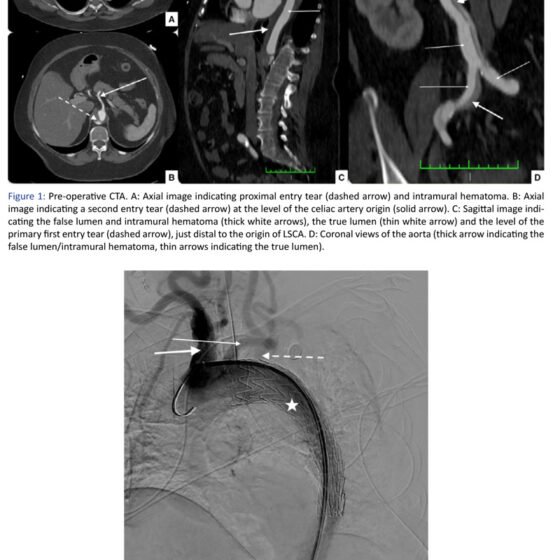

We present a 60-year-old female patient who was admitted from the emergency department due to ATBAD. CT angiography (CTA) indicated ATBAD with the primary entry tear located just distal to the Left Subclavian Artery (LSA) origin, extending distally to the aortic bifurcation and the left common iliac artery. Additionally, intramural hematoma with multiple ulcerations was noted, extending from the level of the LSA to the thoracoabdominal aorta, where a second entry point was also identified at the level of the celiac artery (CA) origin, on the posterior aortic wall. The CA, superior mesenteric artery, and renal arteries were originating from the true lumen (TL), whereas the inferior mesenteric artery from the false lumen, which was patent.

The patient was transferred to the ICU, where the arterial pressure was normalized and the pain was controlled with intravenous antihypertensive and analgesic treatment. During the 2nd hospital day, the patient complained about pain recurrence and underwent repeat CTA without remarkable changes, including expansion of the dissection, rupture of the aorta, or malperfusion to the abdominal viscera or limbs. Because of uncontrolled and refractory pain, she was subjected to emergency TEVAR with LSA coverage during the same day (Gore TAG 34x100mm, W.L. Gore and Associates, Inc.).

The procedure was uneventful. During the 1st postoperative day, the patient was transferred to the ward in good general condition, with orally controlled pain and blood pressure. In the afternoon of the same day, she complained of back pain and underwent a new (3rd) CT angiography, which indicated successful endograft deployment and unremarkable changes in the distal thoracic and abdominal aorta compared to the preoperative imaging. During the same night, the patient became hemodynamically unstable and died. Post-mortem CT examination indicated rupture of the infrarenal aorta and a large retroperitoneal hematoma.

DISCUSSION

ATBAD results in a 13% in-hospital mortality according to previous publications from the IRAD registry, and most of these deaths occur during the first week after the acute event. This was the case with the patient reported here as well, who died on the 1st postoperative day, three days after the initial symptoms. In our case, the patient initially had an uncomplicated ATBAD and was treated with intravenous β-blockers, vasodilators, and morphine. However, due to recurrent and refractory back pain, the dissection was characterized as complicated, and emergent surgical treatment was decided.

Refractory pain is considered a high-risk index after ATBAD, which usually sets the indication for invasive treatment. The term “refractory” has not been clearly defined in the literature, but it is usually considered when it is not possible to control pain for more than 12 hours despite maximal medical therapy. These patients are at increased risk for mortality, especially when managed medically. Specifically, patients with refractory pain and/or uncontrolled arterial hypertension have been shown to present a 35% in-hospital mortality rate compared to 1.5% in the low-risk group when treated conservatively. Although overall mortality (regardless of treatment mode) is again significantly higher among patients with these high-risk variables compared to those without (17.5% vs. 4%), the difference is not as wide, suggesting that invasive management should be considered for these patients. Moreover, periaortic hematoma has been previously identified as a significant predictor of poor prognosis, conferring a relative risk around 3 for death after ATBAD, which was present in our patient.

Current therapeutic protocols regarding invasive management of ATBAD indicate that the procedure aims to cover the primary entry tear to induce positive aortic remodeling. In our case, this was achieved by deploying the endograft just distal to the origin of the left common carotid artery, proximal to the origin of the LSA. This is considered appropriate in cases of acute aortic pathologies, if no specific contraindications exist. Adequate coverage of the primary entry tear and successful deployment of the endograft just distal to the origin of the left common carotid artery were confirmed in the postoperative CTA.

A second entry tear opposite the origin of the CA, feeding the false lumen, had been noted in all 3 CT scans of the patient, but watchful waiting of this lesion was considered appropriate. Covering this would have required more than 35 cm of aortic coverage, with a subsequent risk for neurologic complications, and the origin of the CA would have been covered, while the distal sealing zone till the origin of the SMA would be around 15 mm. These factors, along with the postoperative CTA findings of successful endograft deployment and unremarkable abdominal aorta, contributed to the decision not to undertake a second invasive procedure.

Among the complications after TEVAR for ATBAD are stroke, spinal cord ischemia, retrograde Type A dissection, chronic post-TEVAR aortic dilatation, angulation, migration or collapse of the stent graft, false aneurysm formation, graft erosion, stent-frame fracture, and rupture of the aorta. Perioperative aortic rupture after TEVAR can be classified as procedure-related, device-related, or due to progression of the disease. From the current literature, a low rate of death after endovascular treatment has been reported, mainly due to aortic rupture (two-thirds of cases), most of which are located in the aortic arch after retrograde Type A dissections. We are not aware of previous reports of infrarenal aortic rupture.

CONCLUSION

Acute Type B Aortic Dissection is a vascular emergency requiring urgent treatment. Complicated cases are preferably treated by endovascular means, but even with successful and timely invasive procedures, serious complications may occur, potentially resulting in death. To our knowledge, only scarce data have been reported regarding abdominal aortic rupture after endovascular treatment of ATBAD.

References

-

Murphy MC, Castner CF, Kouchoukos NT. Acute Aortic Syndromes: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mo Med. 2017 Nov–Dec;114(6):458–463. PMID: 30228665; PMCID: PMC6139964.

-

Riambau V, Böckler D, Brunkwall J, Cao P, Chiesa R, Coppi G, et al. Editor’s Choice – Management of Descending Thoracic Aorta Diseases: Clinical Practice Guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017;53:4–52.

-

Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J 3rd, Augoustides JG, Beck AW, Bolen MA, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022 Dec 13;146(24):e334–e482. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001106. Epub 2022 Nov 2. PMID: 36322642; PMCID: PMC9876736.

-

Trimarchi S, Eagle KA, Nienaber CA, Pyeritz RE, Jonker FH, Suzuki T, et al; International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD) Investigators. Importance of refractory pain and hypertension in acute type B aortic dissection: insights from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Circulation. 2010;122:1283–1289.

-

Pape LA, Awais M, Woznicki EM, Suzuki T, Trimarchi S, Evangelista A, et al. Presentation, Diagnosis, and Outcomes of Acute Aortic Dissection: 17-Year Trends From the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:350–358.

-

Evangelista A, Isselbacher EM, Bossone E, Gleason TG, D’Eusanio M, Sechtem U, et al; IRAD Investigators. Insights From the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection: A 20-Year Experience of Collaborative Clinical Research. Circulation. 2018;137:1846–1860.

-

Lombardi JV, Hughes GC, Appoo JJ, Bavaria JE, Beck AW, Cambria RP, et al. Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) and Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) reporting standards for type B aortic dissections. J Vasc Surg. 2020;71:723–747.

-

Matsumura JS, Lee WA, Mitchell RS, Farber MA, Murad MH, Lumsden AB, Greenberg RK, et al; Society for Vascular Surgery. The Society for Vascular Surgery Practice Guidelines: management of the left subclavian artery with thoracic endovascular aortic repair. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:1155–1158.

-

Huang WH, Luo SY, Luo JF, Liu Y, Fan RX, Xue L, et al. Perioperative aortic dissection rupture after endovascular stent graft placement for treatment of type B dissection. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013;126(9):1636–1641. PMID: 23652043.