Rupture of a Juxtarenal Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm after Segmental Artery Embolization before Fenestrated Endovascular Aortic Repair: Review of Literature and a Word of Caution

| Available Online: | January, 2024 |

| Page: | 22-25 |

Author for correspondence:

Ahmed A. Ali

Department of Vascular Surgery – Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, University Hospital, Ludwig Maximilian University Munich, Munich 81377, Germany

E-mail: ahazhar92@live.com

doi: 10.59037/kpakyq52

ISSN 2732-7175 / 2024 Hellenic Society of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery Published by Rotonda Publications All rights reserved. https://www.heljves.com

Abstract

Full Text

References

Images

Abstract

Aim: To highlight the impact of wire and catheter manipulation on aortic wall integrity in minimally invasive segmental artery coil embolization (MISACE) before fenestrated endovascular aortic repair (FEVAR).

Case: An 80-year-old male with a juxtarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm opted for FEVAR due to comorbidities. MISACE was done to prevent spinal cord ischemia (SCI) and type II endoleak before deploying a custom-made fenestrated endograft. Tragically, the patient succumbed to rupture three days post-MISACE.

Conclusion: Although MISACE offers proven and unproven protection against SCI and type II endoleaks respectively, the risks associated with wire and catheter manipulation during the procedure on the integrity of aortic walls remain understudied. Further studies are needed to highlight the impact of such manipulation in complex aortic aneurysms.

Keywords: Juxtarenal aortic aneurysm; Spinal cord ischemia; Endoleak; Aortic Rupture; Case Report.

Full Text

ABBREVIATIONS

CMD = Custom-Made Device; CT = Computed Tomography; EVAR = Endovascular Aneurysm Repair; FEVAR = Fenestrated EVAR; F/B-EVAR = Fenestrated/Branched-EVAR; JRAAA = Juxtarenal Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm; MISACE = Minimally invasive segmental artery coil embolization; SCI = Spinal Cord Ischemia; T2EL = Type II Endoleak.

INTRODUCTION

Fenestrated/branched endovascular aortic repair (F/B-EVAR) is now a valid treatment for juxtarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms (JRAAA), demonstrating outcomes comparable to open surgical repair.1 However, extended proximal aortic coverage poses a risk of spinal cord ischemia (SCI) due to the coverage of spinal segmental arteries, with SCI rates reaching up to 17.7% post-endovascular repair.2

A study by Branzan and colleagues involving 54 patients with thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms highlighted the success of Minimally Invasive Segmental Artery Coil Embolization (MISACE) in preventing SCI, with none of the subjects experiencing it during follow-up.3 MISACE not only protects against SCI but also has a potential role in eliminating type II endoleaks (T2EL), the common presenting endoleaks after F/B-EVAR.4, 5

Despite these potential benefits, we present a case of a JRAAA that ruptured following a MISACE procedure.

CASE REPORT

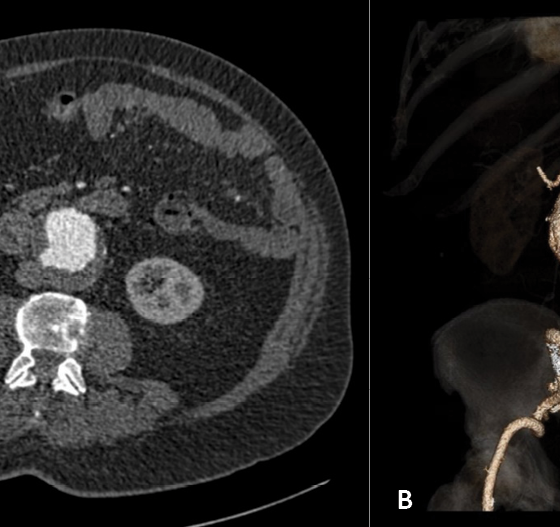

An 80-year-old male with a history of diverticulitis and colonic resection was referred for a growing asymptomatic JRAAA that was first discovered accidentally a few years ago during a computed tomography (CT) scan. CT scan revealed a 59 mm aneurysm with an infrarenal aortic neck length of < 10 mm. Figures 1 A and B show the CT scan of the presented aortic aneurysm.

Open surgical repair was not considered suitable due to cardiovascular comorbidities, and history of previous abdominal surgery. Aortic anatomy was carefully assessed using a dedicated 3D workstation (Aquarius intuition viewer, TeraRecon) and measurements were sent to Cook Medical (Bloomington, IN, USA) to manufacture a custom-made four-fenestrated device.

The endograft would require proximal thoracoabdominal coverage of at least three levels of segmental arteries, each with diameter > 3mm. The patient deemed at risk of suffering spinal cord ischemia during endovascular aneurysm exclusion.

Minimally invasive segmental artery coil embolization (MISACE) is a technique well acquainted at our institution performed by colleagues from interventional radiology for patients considered at risk of SCI before F/B-EVAR. Segmental arteries are usually selected during preoperative planning and intraoperatively according to their diameters. Consequently, it was proposed as a protective measure against SCI before definitive endovascular repair with the added benefit of possible protection against T2EL. The patient’s consent was taken for the MISACE, the proposed aortic endovascular treatment, and the use of data for future studies and publication. The CMD was to be ready in about 8 – 12 weeks.

Two months later, the patient was readmitted and referred to the colleagues of the Interventional Radiology Department for MISACE. Using micro coils, the thoracic T12, and lumbar L1 segmental arteries were embolized on both sides. Figures 2 demonstrate the successful embolization steps of some of the segmental arteries.

The patient was transferred to the intensive care for monitoring. On the third post-operative day, he experienced sudden severe abdominal and back pain. Because of his known history, he underwent immediately a CT scan. Figures 3 A and B reveal a ruptured juxtarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm at the proximal aortic aneurysm segment.

An aortic rupture was visualized, and the patient was immediately transferred to the operative theatre. The patient was quickly intubated while mechanically and medically resuscitated. The femoral artery was punctured using duplex sonography and a guide wire was inserted. Attempts to advance different guidewires and catheters into the proximal healthy aortic segment failed. Despite the maximum efforts of the resuscitation process, adequate circulation was not restored and conversion to open surgery was aborted. Sadly, the medical team documented the patient’s demise.

Postmortem examination was refused by the patient’s relatives, which went in line with the legal and medical authorities at our institution.

DISCUSSION

Juxtarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms, historically managed through open surgical repair, are now often treated with endovascular interventions due to advancements in techniques and experiences. These interventions are particularly beneficial for patients who were previously unsuitable for open surgery or had a high mortality risk.1, 6, 7 In this case, a custom-made FEVAR device was chosen for the patient considering their age, cardiopulmonary status, and abdominal surgical history. These devices typically take 8-12 weeks to manufacture.

Endovascular treatment of juxtarenal aneurysms usually necessitates extended proximal coverage to higher aortic zones for a safe proximal landing zone.7 Hence an increased risk of spinal cord ischemia and possible paraplegia or paralysis. Reports of SCI after endovascular aortic repair have varied and reached as high as approximately 18%2. To avoid such adverse outcomes, many solutions have been proposed including permissive hypertension, CSF drainage, temporary sac perfusion, staging the procedure(s), revascularization, or minimally invasive embolization of segmental arteries before definitive stent graft placement. The main rationale behind occluding these arteries is to precondition the spinal circulation for the forthcoming extensive occlusion, thereby inducing the formation of sufficient collateral arterial circulation to safeguard against SCI.4

Adjunctive measures to protect against SCI involve maintaining higher mean arterial blood pressure, optimizing oxygen saturation, and having adequate hemoglobin levels. Factors that would increase the risk of SCI include elevated international normalized ratio, bilateral iliac artery occlusion, and non-elective procedures.8 In addition, a lumbar drain could be placed, if not already done before, by which the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is aspirated to reduce the CSF pressure and therefore, increase the cerebral and spinal perfusion pressure. However, this increases the risk of complications during drain placement and probable longer periods of stay in the intensive care unit.8

Endoleaks are the most common reported complication following EVAR procedures with T2EL accounting for up to 40 % of them.9 Half of those reported endoleaks are usually self-limiting and require no treatment while the remainder are either persistent or late-onset. Mechanical occlusion of the segmental arteries aims to occlude major thoracic and lumbar arteries to prevent back bleeding after endograft deployment, thereby reducing the chances of having an endoleak type II. It also helps avoid the possible steal phenomenon from the collateral network of the spinal circulation. Therefore, MISACE presents a golden chance to resolve dual objectives simultaneously: SCI and T2EL.

According to the recent ESVS guidelines10, for patients undergoing endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, routine pre-emptive embolisation of the inferior mesenteric artery and lumbar arteries, and non-selective aneurysm sac embolisation is not indicated. While MISACE is generally considered safe, with no reported mortality up to date, it still carries a similar risk of endovascular iatrogenic perforation and rupture.11 In 2018, a study was published addressing the role of MISACE and SCI protection among patients with thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. MISACE was performed before definitive endovascular treatment. Two patients died in the interval period after MISACE completion and before definitive EVAR.3 The dangers of mechanical manipulation on aortic walls leading to serious deterioration are understudied. Although several documented reports and case series have highlighted the association of vessel perforation with guidewires and catheters, such occurrences have not been demonstrated in the aorta.11

Despite the intended protection against spinal cord ischemia and T2EL; guidewire and catheter manipulation in patients with complex abdominal aortic aneurysms might result in serious adverse outcomes. CMD also has a significant long duration period of manufacture that might have seen the aneurysm grow more rapidly and fragile than expected. Despite the absence of a postmortem study confirming the connection between aortic rupture and mechanical manipulation, recent maneuvers make it challenging to dismiss such a causal link. Perhaps, a perforation was induced by the mechanical manipulation that remained indolent before transforming into a frank rupture. The use of upper extremity access could be used in the future for safe manipulation away from the abdominal aortic pathology and minimizing the risks of aortic wall engagement with potential adverse events. Hence, it was imperative to underscore this potential association and issue a cautionary message.

CONCLUSION

Although MISACE offers proven and unproven protection against SCI and type II endoleaks respectively, the risks associated with wire and catheter manipulation during the procedure on the integrity of aortic walls remain understudied. Further studies are needed to highlight the impact of such manipulation in complex aortic aneurysms.

References

- Steffen M, Schmitz-Rixen T, Böckler D, Grundmann RT; DIGG gGmbH. Comparison of open and endovascular repair of juxtarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2020 Mar;405(2):207-213. doi: 10.1007/s00423-020-01865-4. Epub 2020 Apr 8. PMID: 32266530.

- Spanos K, Kölbel T, Kubitz JC, Wipper S, Konstantinou N, Heidemann F, Rohlffs F, Debus SE, Tsilimparis N. Risk of spinal cord ischemia after fenestrated or branched endovascular repair of complex aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2019 Feb;69(2):357-366. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2018.05.216. Epub 2018 Oct 29. PMID: 30385148.

- Branzan D, Etz CD, Moche M, Von Aspern K, Staab H, Fuchs J, Then Bergh F, Scheinert D, Schmidt A. Ischaemic preconditioning of the spinal cord to prevent spinal cord ischaemia during endovascular repair of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm: first clinical experience. EuroIntervention. 2018 Sep 20;14(7):828-835. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-18-00200. PMID: 29969429.

- Addas JAK, Mafeld S, Mahmood DN, Sidhu A, Ouzounian M, Lindsay TF, Tan KT. Minimally Invasive Segmental Artery Coil Embolization (MISACE) Prior to Endovascular Thoracoabdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2022 Oct; 45(10):1462-1469. doi: 10.1007/s00270-022-03230-y. Epub 2022 Aug 4. PMID: 35927497.

- Guo Q, Du X, Zhao J, Ma Y, Huang B, Yuan D, Yang Y, Zeng G, Xiong F. Prevalence and risk factors of type II endoleaks after endovascular aneurysm repair: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017 Feb 9;12(2):e0170600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170600. PMID: 28182753; PMCID: PMC5300210.

- Rao R, Lane TR, Franklin IJ, Davies AH. Open repair versus fenestrated endovascular aneurysm repair of juxtarenal aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2015 Jan; 61(1):242-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.08.068. Epub 2014 Sep 18. PMID: 25240242.

- Doonan, R. J., Girsowicz, E., Dubois, L., & Gill, H. L. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of endovascular juxtarenal aortic aneurysm repair demonstrates lower perioperative mortality compared with open repair. Journal of Vascular Surgery, 70(6), 2054-2064.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2019.04.464.

- Kitpanit N, Ellozy SH, Connolly PH, Agrusa CJ, Lichtman AD, Schneider DB. Risk factors for spinal cord injury and complications of cerebrospinal fluid drainage in patients undergoing fenestrated and branched endovascular aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2021 Feb; 73(2):399-409.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.05.070. Epub 2020 Jul 5. PMID: 32640318.

- Akmal MM, Pabittei DR, Prapassaro T, Suhartono R, Moll FL, van Herwaarden JA. A systematic review of the current status of interventions for type II endoleak after EVAR for abdominal aortic aneurysms. Int J Surg. 2021 Nov;95:106138. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.106138. Epub 2021 Oct 9. PMID: 34637951.

- Wanhainen A, Van Herzeele I, Bastos Goncalves F, Bellmunt Montoya S, Berard X, Boyle JR, D’Oria M, Prendes CF, Karkos CD, Kazimierczak A, Koelemay MJW, Kölbel T, Mani K, Melissano G, Powell JT, Trimarchi S, Tsilimparis N; ESVS Guidelines Committee; Antoniou GA, Björck M, Coscas R, Dias NV, Kolh P, Lepidi S, Mees BME, Resch TA, Ricco JB, Tulamo R, Twine CP; Document Reviewers; Branzan D, Cheng SWK, Dalman RL, Dick F, Golledge J, Haulon S, van Herwaarden JA, Ilic NS, Jawien A, Mastracci TM, Oderich GS, Verzini F, Yeung KK. Editor’s Choice — European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2024 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aorto-Iliac Artery Aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2024 Feb;67(2):192-331. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2023.11.002. Epub 2024 Jan 23. PMID: 38307694.

- Rizk T, Patel D, Dimitri NG, Mansour K, Ramakrishnan V. Iatrogenic Arterial Perforation During Endovascular Interventions. Cureus. 2020 Aug 25;12(8):e10018. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10018. PMID: 32983713; PMCID: PMC7515740.